I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive: Cowboys, Image, and Memory

HENRY KRUSOE 05 September 2020

Writin’

a deep dive into some abstract cowboy theory (yeehaw)

Somewhere in my deepest thoughts

Familiar scenes and memories unfold

These wild and unexplained emotions

That I’ve had so long but I have never told

Like every time I fly up thru the heavens

And I see you there below

I get the feeling sometime

In another world I lived in El Paso.

-Marty Robbins, “El Paso City”

In the essay “Photography,” Siegfried Kracauer demarcates photography’s relationship to time,

memory and meaning. For Kracauer, meaning, is expressed by the memories of individuals and

collectives, but these memories arise from processes fundamentally unlike a those which produce a

photograph. One’s memory of their grandmother is not an unbroken record of the traits and images of a

particular woman. Further, while the entire continuum of information that emanated from one’s

grandmother may be out of reach, a memory is not even a complete archive of the available information.

A memory is a certain composition of the available information, a warped and partial glimpse of the

“complete” record. The personal experiences, secondhand stories, family legends, gossip, and artifacts

associated with the grandmother are processed and picked over to create the memory of the woman.

Memories are highly selective with respect to the available information and even the fragments that are

chosen are not left unchanged. The memory is formed from fragments which are subject to “repression,

falsification, and emphasis.” All memories are formed by these processes, no matter the object, and

regardless of whether they belong to an individual or a collective.

In Haunting Legacies: Violent Histories and Transgenerational Trauma, Gabriele Schwab describes the individual and collective processes of memory that apply to traumatic experiences and histories. She writes about the power of words and stories, which can “encrypt” traumatic experience in memory. Encryptment occurs through same processes of repression, falsification, and emphasis identified by Kracauer. These processes “seal over violent ruptures and wounds,” created by trauma. The internal motivations which direct the formation and encryption of memory are summarized by what Kracauer calls the “life of the drives.” These drives include natural predispositions, romantic ideals, social conditioning, politics, and historical inertia. Put simply, the life of the drives is simply the collection of forces which take an interest with the appearance of memories, while seeking to modify and compose them. In the case of memories of trauma, past violence is processed and composed into a “haunted language.” Schwab writes, “As a rule haunted language has vacated the emotions, the pain and terror, pertaining to the silenced history. As a result, it has become empty speech, either coldly detached and abstract or filled with a false emotional ring.” While Schwab investigates the creation of memory with language, and Kracauer writes about memory formation in visual terms, a comparison can be drawn between “empty speech” and what Kracaur calls “the transparency of the final memory image.” This final memory is “the last image,” of the object, the image which is “unforgettable” and constitutes that object’s “actual history” This history gives us a view of the meaning we seek, precisely because that meaning settles the drives. If the object is traumatic experience, it is the memory which has vacated unwanted or unbearable emotions of pain, terror, and shame. By virtue its finality, the history ultimately produced by bending and warping is the most bearable composition of experience, including only what is “unforgettable.” Incorporating Swab we may also say it is the image that arrives at the end of encryptment.

We see now see how Kracauer’s vocabulary of transparent images and the unforgettable nicely complements Schwab’s investigation of encryptment and silencing. Schwab expands Kracauer’s account of memory and meaning by demonstrating the disturbing extent to which trauma can be encoded memory, and thereby forgotten. To this end, Schwab quotes W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz: “I knew nothing about the conquest of Europe by the Germans and the slave state they set up, and nothing about the persecution I had escaped.” Even the most extreme and thoroughly lived experiences of trauma, those that have such force and presence that they seem completely indestructible, are ultimately, even necessarily, forgettable. For Schwab, this kind of forgetting can occur through encrypting forms of storytelling which facilitate the creation of the final image through secrecy, selection and embellishment.

By synthetizing Kracauer and Schwab, an account of memory production is articulated which addresses both visual and literary encryption. This account may be applied with unique success to the figure of the American cowboy in country and western music, a character which spans a vast lineage of visual incarnations. In the context of country music, Schwab’s analysis of words and stories becomes invaluable; when the cowboy appears, he is always already singing.

The cultural and visual phenomenon of the cowboy is born from the historical reality of the working cattle hand of the 19th century, although one sees only a modest resemblance between the two. Pual H. Carlson, in “Myth and the Modern Cowboy” writes how “real cowboys were dirty overworked laborers,” and the actual word “cowboy” was often equated with cattle theft and immorality during the late 19th century. The golden age of “real cowboys” ended with the invention of barbed wire and the ensuing enclosure of “the open range” at the end of the 19th century. While the profession of cattle hands still endures today, this marked the fundamental demise of the cowboy that inspired nineteenth-century pop culture: minstrel shows, dime novels, and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows. The 20th century image of the cowboy evolves from the continual refinement and reshaping of the vestiges of that popular media, which itself presented a highly encrypted image of the cowboy.

In the early 20th century, movies and songs revived and popularized a figure who’s costume loosely resembled a real cowboy, but departed from the historical cowboys’ poverty, dirtiness, and impropriety. Further, the reality of the cowboy as a multicultural and multiracial profession, one which included African American, Hispanic, and Native American cowboys, is erased. The imaginary cowboy, and those who embody him, are white men with startlingly few exceptions, even today. Carlson describes how “western films, pulp novels, and radio shows continued until the cowboy changed from rogue to hero. We have it seems, sort of corrupted him in reverse. We have made him better than he was.” The result of this erasure and encryption is “the last image” of the cowboy, one that obliterates of any connection between the cowboy and corresponding histories of violence, race, discrimination and oppression in the 19th century. As Kracauer states, this last image becomes the figure’s history, the memory that eclipses the more complicated and forgettable traces of the cowboy which actually roamed the Western territories.

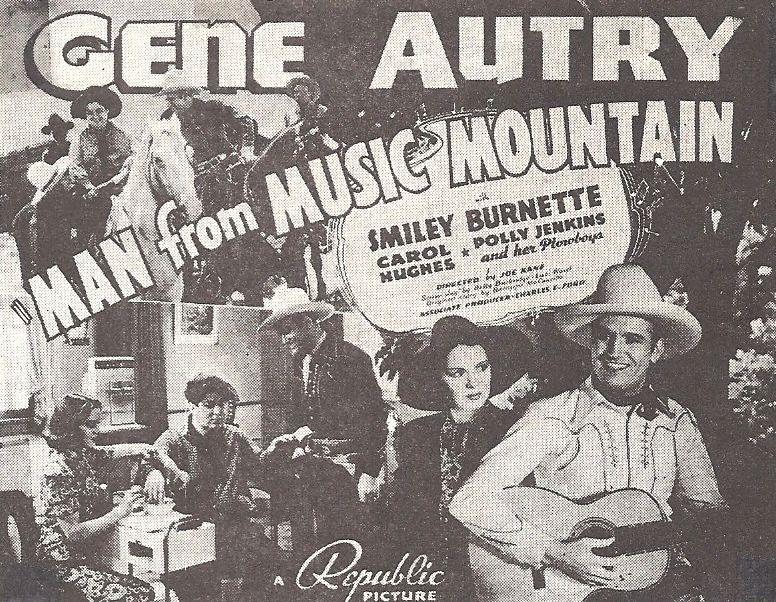

Gene Autry played a fundamental role in promoting this image of the cowboy. In Public Cowboy No. 1 : The Life and Times of Gene Autry, Holly George-Warren describes how Autry “merged old sensibilities with new ideas to create a persona that bridged the gap between the two centuries.” Through records, radio shows, and movies (he appeared in ninety films, usually playing the lead role as the singing cowboy) he help solidify the cowboy as a memory image enshrined in American culture. In his films, Gene Autry appears “as himself,” unstuck from time and transported into falsified western past to help the denizens of the old west defend themselves from robbers, frauds, and villains of all descriptions. Johnny Cash, a man who became a country music star after being inspired by Autry’s movies as a kid, described Autry’s movie persona as “a handsome man on a fine stallion, riding the bad trails of this land, righting wrongs, turning good for bad, smiling through with the assurance that justice will prevail.” This persona doubles as the mouthpiece for Autry’s innumerable trail songs and western ballads, extending its visual power into the musical dimensions. Autry’s films had raw aesthetic and moral appeal. They erased any uncomfortable or ugly features of the American West while promoting an alternative, wildly positive, image of American heroism. These features made Autry’s cowboy irresistible to audiences. Johnny Cash declares, “Reflecting upon . . . the great people I have known, as an All- American image of goodness, justice, good over bad, nothing or no one comes closer than Gene Autry. [my italics]” The success of that image spawned an orgy of imitation which continued profitably until the mid 1950s when the image of the family-friendly cowboy and its songs began to wane. When fashionable, Autry’s songs and films enabled Americans to easily see an image of national goodness and justice. This image masqueraded in the costumes of a falsified past but reflected the values and hopes of a contemporary audience. Autry’s cinematic conjuring of the singing cowboy created an appealing ensemble of images, props and narratives that served a positive (and highly marketable) image of America’s past and present.

When Autry’s specific brand of cowboy fell out of fashion in the mid 1950s, it gave rise to innumerable variations and subspecies. Starting during late 1950s, Marty Robbins recorded love songs and gunfighter ballads that modified Autry’s heroic (almost saintly) cowboy into a man less constrained by morality and propriety, one capable of greater feats of violence and carnal romance. Autry’s vibrant and highly accessorized costume of the cowboy slowly disintegrates, although its core accessories, the signature hat and boots, remain. Robbins liked to perform in Italian-made three-piece suits. A reporter asked him in an interview “Why don’t you wear cowboy clothes?” and remarked that he looked like “a cowboy in a continental suit.” Soon after the interview was published, Marty Robbins released the single, “The Cowboy in the Continental Suit.” The song tells the story of a cowboy who conquers an unruly horse in a three-piece suit. By projecting his own sense of style back onto the figure of the cowboy, he showed the almost limitless capacity of the figure to accept such anachronisms. The song sounds “authentic,” even though the cowboy incorporates clothes into his costume which won’t be fashionable for another 70 years.

The image of cowboy continued to bend and warp according to lives of the singers who carried it forward. In the 70’s stars like Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and Kris Kristofferson updated the cowboy image which preceded them into the “outlaw” persona, which merged western imagery with the rowdier public persona of public contemporary song writers. In 1994, these four country stars met with Gene Autry to collaborate on a cover of his classic song, “Back in the Saddle Again.” Their producer remarked that seeing the stars together revealed how each of the them had “adopted variations on the cowboy persona, and that’s the guy they got it from.”

The cowboy has persisted in the songs and personas of country musicians to this day. Throughout this process, the cowboy’s costume and the coherence of western narratives has gradually disintegrated. In the 1990s, Garth Brooks released the two best-selling country albums of all time. Although their titles “Ropin’ the Wind” (where has the cow gone?) and “No fences” both reference the “real” imagery and history of 19th century cattle ranching, the same can be said for only a fraction of its content. The cowboy’s last image has become increasingly compact, tasked with encrypting the innumerable fashions which have facilitated its presentation in the past but become increasingly unsightly over time. The enduring symbolic value of the cowboy as a figure that represents “freedom, independence, strength and action” becomes compressed into the two remaining pieces of his costume that have remained consistent throughout its lifetime: the hat and books. At one point, Garth Brooks was scheduled to appear at a major festival event to sign autographs and mingle with fans, but failed to arrive. In his stead, he sent along his boots, hat and shirt, along with a cardboard cutout bearing his likeness. Fans were invited to wear Brooks’ clothing and take pictures with his cardboard likeness, communing with the cowboy in a purely symbolic realm, where even the “live cowboy” was ultimately unnecessary for aesthetic satisfaction.

Each new cowboy must be recomposed and re-encrypted until he is once again fashionable. This is the condition of his commercial success. This unending revision is caused in part by the cowboy’s heightened reliance on costume, which tend to age faster than the cowboy’s abstract symbolic appeal. Every past cowboy satisfied certain desires and romantic notions, cohering to the prevailing ideals of America and white masculinity of its time. Cowboys became barroom fighters, secret lovers, soldiers, artists, philosophers, and “modern day drifters” as needed. As the image of the cowboy gets older, more and more fashions and symbolic variations are accrued, an overflowing reservoir of unfashionable cowboys which become encrypted in the latest iteration. New cowboys must discard all that was “forgettable” and hence “unfashionable” about all that came before, while retaining or reviving those fashions which hold enduring of nostalgic value. One particularly unholy example of this reverberation and revival can be heard in the album, “Three Hanks.” Using digital manipulation, Three Hanks joins together in song the voices of the long-dead honky-tonk legend, Hank Williams, his son Hank Williams Jr., who also became a popular country singer, and his grandson “Hank the Third,” who also entered the musical profession. Their voices, forcibly joined together across time, sing together in strained synchronicity. Uncannily, the synthetic and death-defying trio reprise one of Hank William Sr’s classics, “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive.”

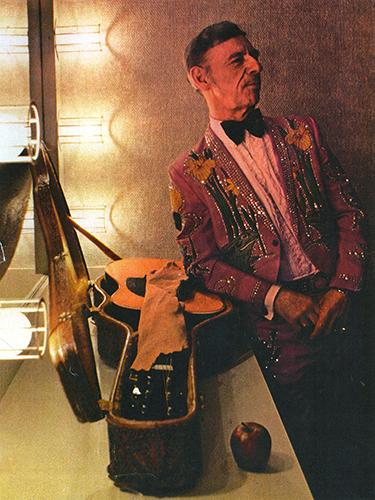

When we look at photographs of the country and western musicians who have embodied the cowboy, we find the images which time has made both unsightly and nostalgic. Revisiting Gene Autry’s movies reveals ridiculous costumes and campy scenarios, but also discloses a certain persistent charm. The same can be said of the various costumes and fashions incorporated into the cowboys of Marty Robbins, and the outlaws. Looking back from 2020, even Garth Brooks’ relatively recent formula for the cowboy of the 1990s seems pathetically out of fashion. Kracauer describes the antagonistic relationship between fashion and photography. What is easily forgotten by people is held fixed and shamefully visible in the photograph or the recording. The old (but not yet nostalgically old) photograph betrays both the viewer and the cowboy. “The image proves that alien trappings were incorporated into life as accessories.” It brings a horrible discrepancy to light. The images of past cowboys were buried and laid to rest with the knowledge that they “were fashionable.” In photographs, they appear to us again not only as ghosts, but as unfashionable ghosts. The viewer reels back in surprise exclaiming “That was Americans thought a cowboy looked like?” The photograph shows us the “far from necessary” nature of past incarnations of the cowboy and thus casts unwanted suspicions on those that happen to be currently fashionable.

Hank Snow with his “Frog Suit”made by Nudie Cohn, 1969

Hank Snow with his “Frog Suit”made by Nudie Cohn, 1969

Highwayman 2, 1990

Highwayman 2, 1990

These photographs invite us to compare past and present images of cowboys. Seen collectively, they reveal an incoherent cast of white men in costumes that have lost transparency. When we compare photographs of Gene Autry, Willie Nelson and Garth Brookes, we see that the image of the cowboy is full of jumps and gaps. A hundred different men have embodied a hundred different versions of the cowboy. They all become, as Schwab describes “buried ghosts of the past come to haunt language from within, always threatening to destroy its communicative and expressive function.” Even though the songs that compose Country music’s long and multigenerational history coexist relatively peacefully in the ears of most C&W fans, the various cowboys, each clad in their signature cowboy outfit, would never be able to share the same stage without betraying the comical and exotic breath of their menagerie. Even though visual synthesis seems virtually impossible, the collective voice of these ghosts speaks from a place unstuck from time and struggles to find the words it wants. It is muffled and cacophonous, but I believe it is still possible to find a cohesive message through the static. If meaning is understood as the enduring features of memory, then perhaps the message of this collective voice lies in his most consistent features: his ethnicity, gender, nationality, his hat, and his boots. His most stripped down and reduced description becomes his meaning. The cowboy is a lonely white American man longing for wide open spaces. He wears a hat and boots. His persistent reappearance and revision across time signifies the persistent desire to make such a persona fashionable and unforgettable. After the death of Marty Robbins, his wife disclosed, “I made a promise to Marty before he died—one of his biggest fears was to be forgotten—and I promised him I would do everything in my power to see he wasn’t forgotten.” In Gene Autry twilight years, perhaps driven by fears like those of Marty Robbins’, he invested $100 million to establish the “Autry Museum of Western Heritage,” in Los Angeles. The museum’s mission, according to Autry, was to “exhibit and interpret the heritage of the west and show how it influenced America and the world.”

Yet country music stars are not the only ones who desire the longevity and renewal of the cowboy. Kracauer writes that “the new fashions also must be disseminated, or else in the summer the beautiful girls will not know who they are.” Each cowboy is always crafted for its audience. His fashionably and circulation are determined by his ability to satisfy and entice the community that consumes him. Lawrence Clayton writes about the enduring image of the cowboy. Echoing Kracauer, Clayton writes, “the figures refuse to disappear because it appeals to a subconscious yearning that many of us steadfastly –perhaps romantically– refuse to give up completely. It wells from so deeply within us that without it and our other myths we could not exist.” The cowboy has appeal because he tells us who we are, but who is “we?” One might broadly say Americans. Gene Autry’s cowboy showed us “all- American goodness,” and in so doing made it possible for Americans to see themselves capable of such goodness. Yet we may also say that the cowboy’s audience is more specific, composed of white American men like himself. Cowboys frequently give these men identities which they long to have. The cowboy is free. He is a good lover. He is powerful. He may inflict violence at his discretion. He is successful. Even if the image isn’t wholly positive (country and western songs are riddled with drunks, losers, and horrible mistakes) even in this instances men can still identify with the cowboy’s image and emotions.

One last question remains. Distinct from the live performer and his audience, what does the image of the cowboy want? Does he want to always be remembered? Does he also want to know himself? Do we take him at his word when he sings “Don’t fence me in?” In his essay, “What do Pictures Really Want”? W. J. T Mitchell writes, “What pictures want is not the same as the message they communicate or the effect they produce; it’s not even the same as what they say they want. When we see the state of the cowboy today, we glimpse a figure which has become less and less meaningful over time, yet nonetheless is clung to as a necessary culture fixture. He continues to be scattered and stretched into new bodies, costumes, geographies, and times, with no foreseeable end in sight. Swept up in the ceaseless churning of American pop culture, the cowboy seems doomed to a slow process of disintegrating circulation that will never end. Perhaps, in time, even his hat and boots will also be subtracted from his image. So what does the cowboy want? Schwab provides us with one answer. She writes how “the body that becomes the site of narration… can waste away to speak the wish to die.”